There aren’t many careers where an individual can dedicate their lives and not end up with any long-term benefits — whether it be healthcare, a pension, or the like. Hip Hop happens to be one of those industries. Artists who dedicate their lives to the culture may find themselves in precarious situations down the line.

This is where the concept of a union of sorts has — on more than one occasion — come into the conversation. Not so much a governing body that would ensure order is kept from a business sense, but rather a way to ensure that, when necessary, a unified force could rally behind individuals who have spent their lives furthering a culture that many us have come to accept as life.

Think health insurance meets worker’s comp.

In August’s second season premiere of Drink Champs, hosted by N.O.R.E. and DJ EFN, LL Cool J stopped by to drop some Hip Hop gems. During the show’s outro, N.O.R.E. brought up the subject of creating a rapper union, which would help to protect the mental and physical well-being of our culture’s greatest contributors.

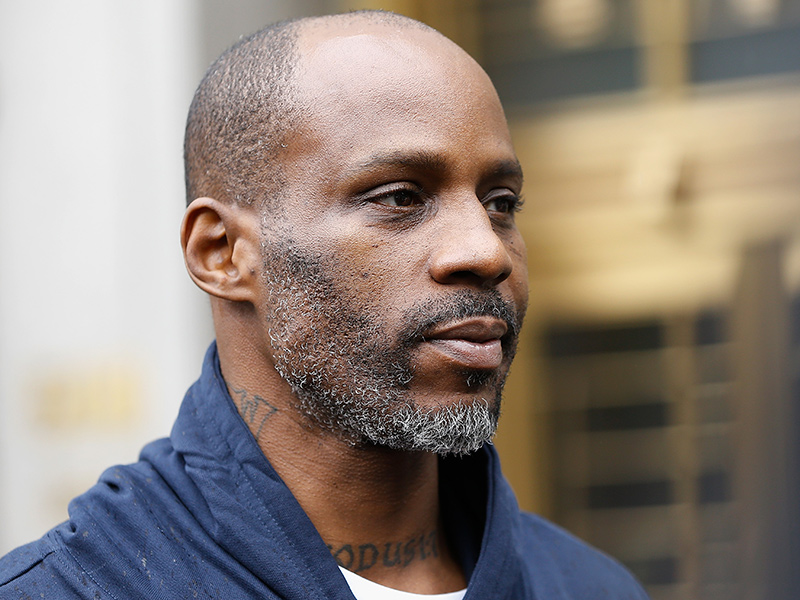

When talking about DMX, N.O.R.E. said, “Isn’t it Hip Hop’s responsibility to say, ‘This man gave us 10 million records … Why don’t we just come and take him and put him into rehab or whatever he needs to do to be safe’?”

AD LOADING...

“Shouldn’t we take 1% of something so if [an event] like Chris Lighty’s passing happens, [his daughter] Tiffany doesn’t have to worry?” N.O.R.E. asked rhetorically. “We can take care of that … Hip Hop owes that to Hip Hop.”

If you’ve listened to the Mogul podcast, which chronicled the life and death of iconic music mogul Chris Lighty, you’ll recall that at the time of his death, Lighty had immense financial trouble. As the show noted, he had a massive tax bill that is still outstanding.

That’s a significant financial burden to leave to your loved ones. Lighty, though, was an example of an executive on top of the game. What about those who never reach that plateau?

While many artists have weathered the changing tides of the industry and managed to create a strong sense of financial security, many of the golden era veterans either fell on hard times or simply weren’t as well off as they appeared. A common misconception is that a million sales equated to a million dollars in the artist’s pockets.

AD LOADING...

The late Sean Price is a great example. While hardworking and widely revered, his funds were largely based on his daily grind. After his death, Duck Down Records created a crowd-funding campaign to mobilize fans to help his family. A similar campaign was set up for underground legend Pumpkinhead upon his death, which was largely an attempt to help cover funeral expenses.

Imagine if there was a fund, as N.O.R.E. described, that would simply step in unprompted and take care of the families of these artists? Perhaps 1% of all album sales could help fund it.

Around seven years ago, the godfather of Hip Hop, DJ Kool Herc, was desperate for a vital operation that cost $40,000 — mere months after fighting to preserve 1520 Sedgwick Avenue, the birthplace of Hip Hop, from foreclosure. The fact that Herc had to make an urgent plea for help was a terrible thing.

The toughest hill to climb here is turning the idea into a reality that actually works. As LL Cool J expressed to N.O.R.E., such a governing system would require an enormous amount of both structure and transparency.

AD LOADING...

“I wouldn’t want my stack to go toward some new Low Pro tires,” he joked.

The structure is likely the biggest obstacle to such a safety net. Who’s eligible to become part of such a union? What will and won’t be covered? LL Cool J noted that artists might only have a few hits, to which N.O.R.E quickly clapped back, “I’m talking about veterans.”

LL was quick to note that Rob Base and DJ EZ Rock only had a few hits, which forced N.O.R.E to slightly concede. LL also noted that ground-level artists might be grateful for a system that could provide basic health benefits for them and their families.

“You’re not going to be successful if you don’t give,” LL explained.

AD LOADING...

This general philosophy definitely could apply to the longevity of our culture, even if only applied to our veterans. DMX, who was the catalyst for the conversation, is a great example. He is a voice that many find synonymous with their formative years. It’s not crazy to think that for all he’s given the culture, the same culture can return the love when he’s at his lowest point.